In 2004 - four Presidential election cycles ago - the website JibJab posted a wildly popular video in which animated versions of then-candidates John Kerry and George W. Bush engaged in a folk-song-rap-battle to the tune of Woody Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land." In JibJab's altered lyrics, Kerry accuses Bush of being a "right-wing nut job" who "can't say 'nuclear,'" and Bush responds that Kerry is a "liberal wiener" who "has more waffles than a house of pancakes." It escalates from there ... a la Tupac vs. Biggie. If you look back on 2004 as a time when civil discourse reigned supreme in our politics, think again. After all, that was the election that gave us the word swiftboating. JibJab employed Guthrie's song - considered by many Americans to be an expression of the ideal of national unity (even if that was not Guthrie's intended meaning) - as a vehicle to comment on the election's nastiness and divisiveness. After the video went viral, Ludlow Music, the music publisher that claimed to own the copyright in Guthrie's song, sent a cease and desist to JibJab, alleging copyright infringement. JibJab, with the help of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking a declaration that Jib Jab's use was a fair use parody.

You can never predict the course a lawsuit will take, how the judge will view your arguments, whether the jury will go your way. Your adversary makes some moves you anticipated, others you didn't (but that you can deal with on the fly), and, every now and then, she throws you a total curve ball. EFF did precisely that when, in the course of preparing its fair use defense, it made a discovery that it believed demonstrated conclusively that "This Land" had fallen into the public domain as early as 1973. If EFF was right. not only would Ludlow lose the case against JibJab, it would lose the whole enchilada: its exclusive right to profit from the song, and the ability to prevent the likes of JibJab from soiling Guthrie's legacy.

, determining the public domain status of a work can be a murky task, requiring interpretation of arcane aspects of expired copyright laws and international treaties, and sleuthing to uncover evidence demonstrating when, where and how a work was published originally. So ... buckle your seat belt. I'm going to make this as simple as possible.

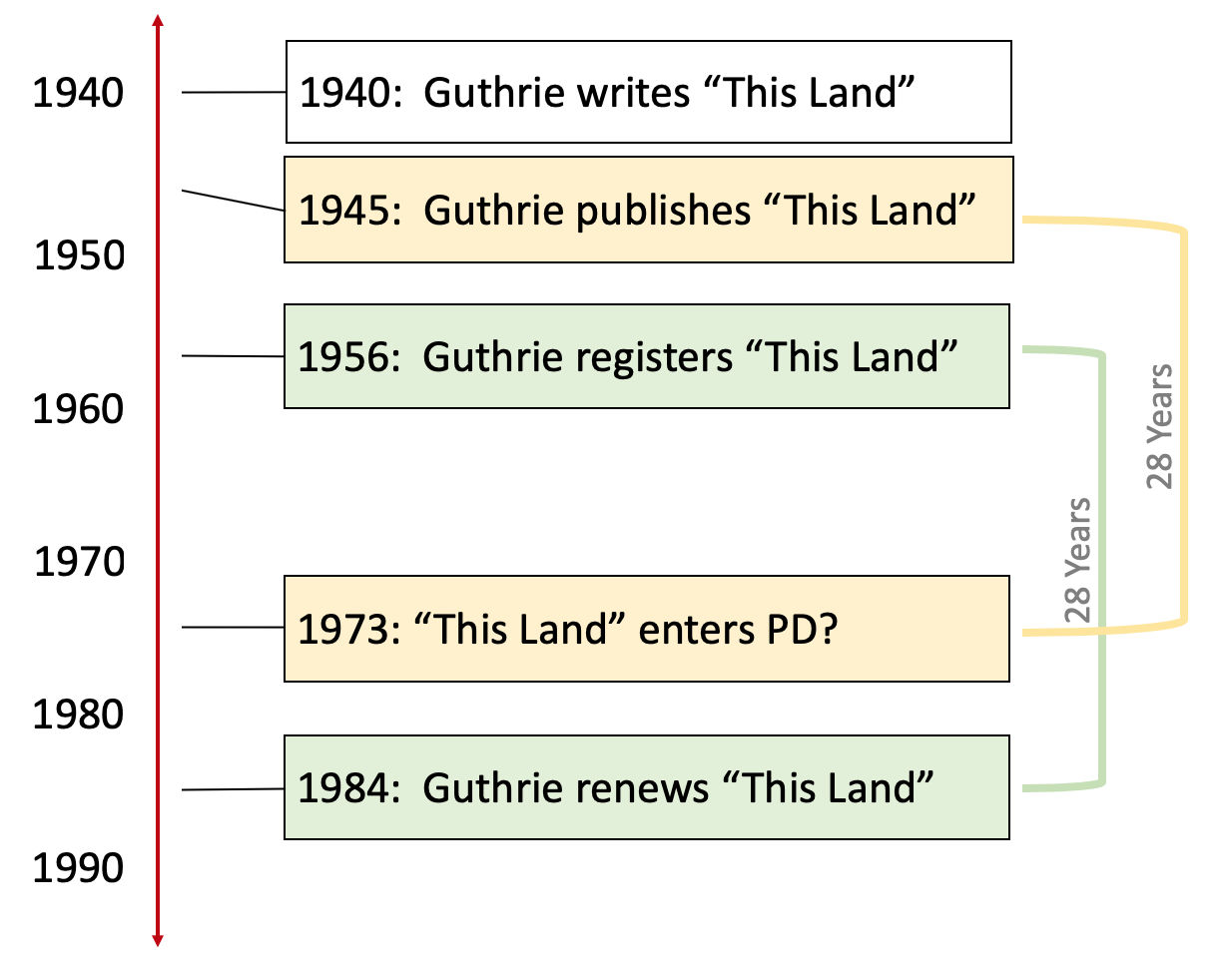

Under the Copyright Act of 1909 (the copyright law in effect when Guthrie wrote "This Land"), the term of copyright was 28 years, renewable once for an additional 28 years. For a composition like "This Land," the copyright term began when the song was published as sheet music, not when it was performed live. In1956, Ludlow obtained a registration for "This Land" as an unpublished work with the Copyright Office (Reg. No. EU432559). Ludlow filed for a renewal in 1984, 28 years after 1956.

However, following up on tips provided by musicologists, EFF discovered evidence that Guthrie had published and sold the sheet music for "This Land" in a songbook in 1945, 11 years before Ludlow registered the song as an unpublished work. The 1956 application for registration makes no mention of this prior publication. Here is the cover page from the song book, listing "This Land" as one of the included songs, and bearing a copyright notice (©1945) on the lower right hand side:

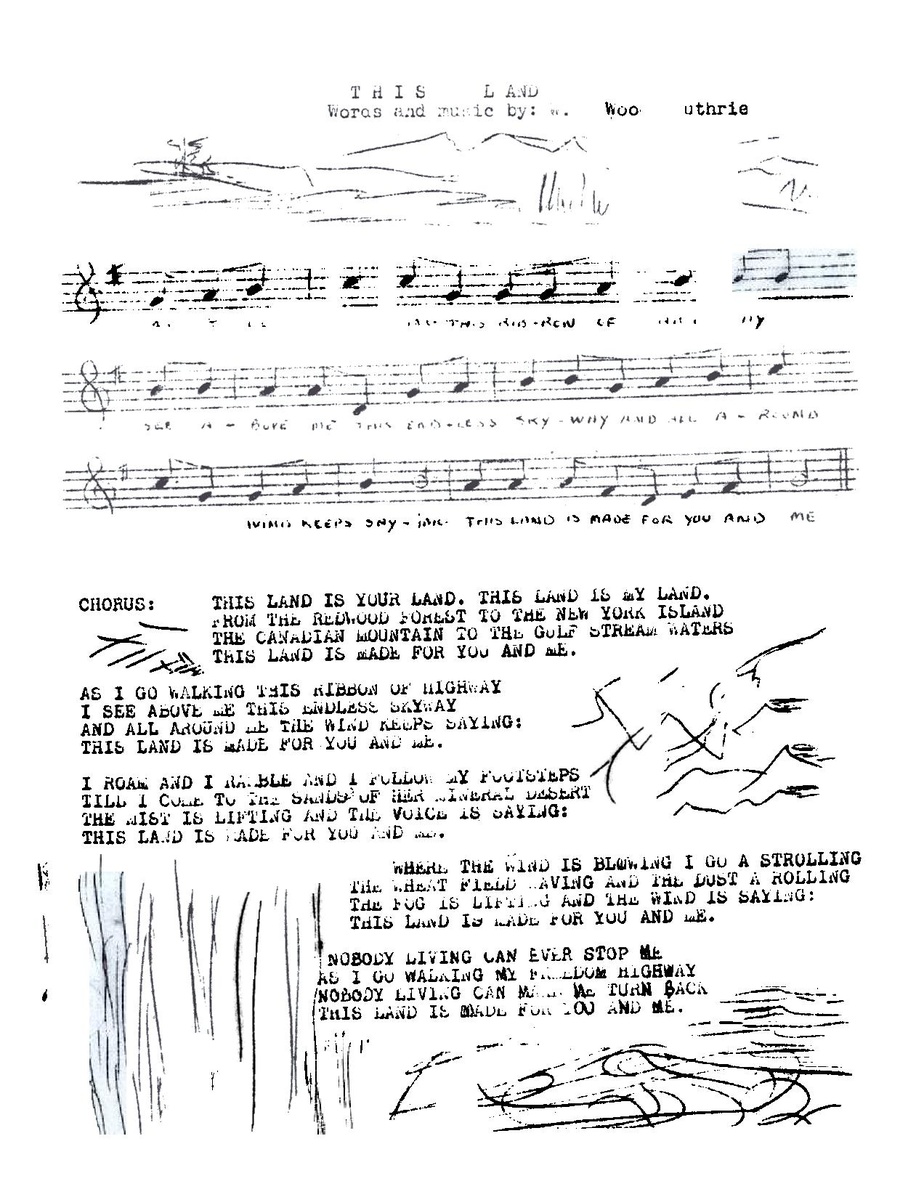

And, here is the page from the songbook with the lyrics (with some differences from the version we learned in Kindergarten) and basic melody for "This Land:"

Based on the evidence that Guthrie published "This Land" in 1945, EFF concluded that the copyright should have been renewed in 1973 (1945 + 28 years = 1973). If EFF was correct, this meant that Ludlow's attempted renewal in 1984 was eleven years too late, and the song fell into the public domain during the Nixon administration.

Based on the evidence that Guthrie published "This Land" in 1945, EFF concluded that the copyright should have been renewed in 1973 (1945 + 28 years = 1973). If EFF was correct, this meant that Ludlow's attempted renewal in 1984 was eleven years too late, and the song fell into the public domain during the Nixon administration.Here one final image that graphically shows the relevant dates:

Ludlow reportedly disputes that the 1945 songbook qualified as a "publication" under the 1909 Act. According to interviews given by Ludlow's lawyer, the publisher has “never seen any indication that copies of this thing were sold by Woody to the public" and instead believes that "at the most, [Guthrie] gave one or two to Alan Lomax, who was his record producer [and] gave one maybe to a manager.” The issue, however, was never battle tested because Ludlow settled with JibJab on terms that (according to an EFF press release) allowed JibJab to continue distributing its video "without further interference from Ludlow."

But this was not the end of the story. In 2016, a Brooklyn band called Satorii sued Ludlow on behalf of themselves and a class of musicians and others who had "entered into a license with Ludlow, or paid Ludlow, directly or indirectly, a royalty or licensing fee for 'This Land' at any time since 2010." The plaintiffs sought a declaratory judgment that the copyright in "This Land" was invalid and that the song had fallen in the public domain, and they demanded a refund of all amounts paid by class members to Ludlow since 2010. (Their lawyers also were behind lawsuits challenging the copyright status of “Happy Birthday” and “We Shall Overcome.") The band's complaint tracks the argument made by EFF, but ups the ante by also arguing that (1) neither Guthrie nor Ludlow ever owned a valid copyright in the melody of "This Land" because it was not original to Guthrie but instead was substantially identical to a Baptist gospel hymn from the late 19th or early 20th century, and (2) the version of the lyrics included in the 1945 songbook entered the public domain in 1951 when they were published, as liner notes, without a proper copyright notice. (Under the 1909 Copyright Act, publication without notice generally resulted in the work entering the public domain.) These people meant business! #brooklynfierce

We've had two reported decisions in this case, neither on the merits. In a 2019 decision, the district court in the Southern District of New York refused to dismiss the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, finding that there was a valid case and controversy because Ludlow was likely to commence litigation against the plaintiffs if they released a new recording of "This Land" (without paying the statutory mechanical license) or a music video featuring the song (without securing a synch license from Ludlow). However, two weeks ago, the court dismissed the case because Ludlow had provided the plaintiffs with a "broadly-worded covenant not to sue" and had tendered a full refund of the compulsory mechanical licensing fees previously paid by the plaintiffs (totaling a whopping $45.50), To reach this result, the court relied on the Supreme Court’s decision in Already, LLC v. Nike, Inc., 568 U.S. 85 (2013) (a covenant not to enforce a trademark against a competitor’s existing products and any future ‘colorable imitations’ moots the competitor’s action to have the trademark declared invalid). We will have to see whether the plaintiffs appeal.

So ... what is the copyright status of "This Land"? Headlines covering the dismissal (such as the New York Times' "'This Land is Your Land' is Still Private Property") are misleading because the court never reached the merits. And maybe no court ever will, if Ludlow continues to settle cases and offer covenants not to sue, when pressed by litigious musicians or public domain vigilantes.

Saint-Amour v. Richmond Organization, Inc.,

2020 WL 978269 (S.D.N.Y. Feb 28, 2020)

Saint-Amour v. Richmond Organization, Inc.,

388 F. Supp. 3d 277 (S.D.N.Y. 2019)

unknownx500

unknownx500