O’Shea Jackson, better known as Ice Cube, is a man of many talents: rapper, actor, director, entrepreneur, and social activist, to name but a few. In 1992, three years after leaving N.W.A., he released the single “Check Yo Self” which featured the line “check yo self before you wreck yo self.” (A remix that uses the beat from Grandmaster Flash's iconic "The Message" was released at around the same time and belongs on your daily playlist.) According to his complaint, the phrase “Check Yo Self” has become Ice Cube's “signature catchphrase.”

Robinhood is a financial-services company that offers a stock trading app and touts "a mission to democratize finance for all." In furtherance of that mission, Robinhood publishes a daily newsletter called “Robinhood Snacks” that provides its readers (a.k.a. "snackers") with, as its motto says, "digestible financial news." The newsletter - characterized by Ice Cube as an "advertisement" - has (according to the court) a "breezy, colloquial tone" and is peppered with pop-culture references.

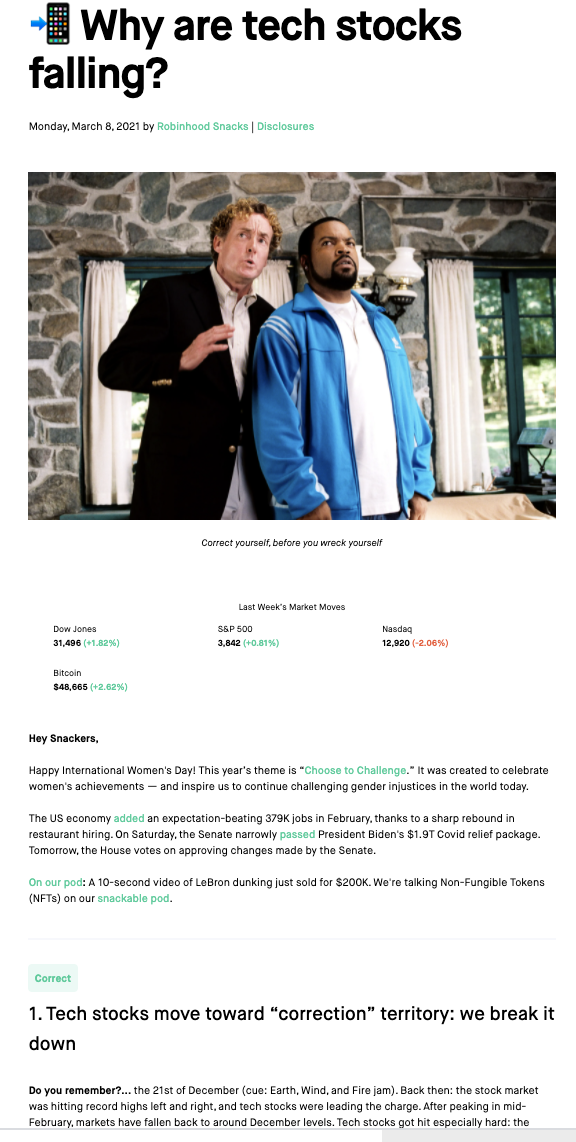

Case in point (and the subject of the lawsuit): the March 8, 2021 edition (available here) used a photo of Ice Cube from the movie Are We Done Yet? to illustrate an article about a market correction for tech stocks. The photo is captioned “Correct yourself before you wreck yourself," an obvious play on the lyrics from "Check Yo Self" and nod to the subject matter of the article it accompanies. Here is a screen grab:

Ice Cube sued, alleging, inter alia, that the newsletter created the false impression that he was associated with or endorsed Robinhood’s services, in violation of § 43(a) of the Lanham Act, and that Robinhood had appropriated his name and likeness for advertising purposes, without his consent, in violation of Cal. Civ. Code § 3344(a) and California common law. Robinhood moved to dismiss the complaint under FRCP 12(b)(1) for lack of standing and under FRCP 12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim. Magistrate Judge Laurel Beeler, in the Northern District of California, granted the 12(b)(1) motion.

To defeat a 12(b)(1) motion, a plaintiff is required to plead facts to support that standing exists, specifically, that (1) the plaintiff suffered an injury in fact, (2) the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged conduct of the defendant, and (3) the injury is likely to be redressed by a favorable judicial decision. To establish an injury in fact, a plaintiff must show that she/he/they suffered an invasion of a legally protected interest. Here, Ice Cube contended that his allegations supported that he had suffered an injury in fact because Robinhood's use of his distinctive, celebrity identity in an "advertisement" implied his endorsement of Robinhood’s products. See, e.g., Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc. (“A celebrity whose endorsement of a product is implied through the imitation of a distinctive attribute of the celebrity’s identity has standing to sue for false endorsement under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.”). Robinhood countered that the complaint was insufficient because no facts were alleged to support that Ice Cube had achieved "celebrity status" or that Robinhood’s conduct had misled consumers into thinking that Ice Cube endorsed its product.

The court rejected Robinhood's bizarre argument that Ice Cube hadn't alleged facts to support his celebrity status. ("But why would Robinhood use the image and a paraphrase of the catchphrase if it did not capitalize on Ice Cube’s celebrity status?") However, the court agreed that Ice Cube had not plausibly alleged that Robinhood's use of his identity constituted an endorsement. According to the court, Robinhood's use of Ice Cube’s picture and a paraphrase of his catchphrase was merely "to illustrate an article about market corrections" and did "not suggest that the plaintiff endorsed Robinhood." The court's holding turns on its assessment that this use occurred in a publication that was a newsletter and not an advertisement. In the court's words:

The plaintiff characterizes the newsletter as an advertisement, not a newsletter. But he attaches the newsletter, which is demonstrably not an advertisement. No case establishes Article III standing under similar circumstances. To the contrary, the cases (cited above) all involve explicit endorsements.

The court gave the plaintiff leave to file any amended complaint within 21 days, so I suspect that we have not seen the end of this.

A few observations:

The court dismissed the entire complaint because Ice Cube had failed to allege "how Robinhood’s use of his identity created the misapprehension that the plaintiff sponsored, endorsed, or is affiliated with Robinhood." While confusion as to endorsement or affiliation is an element of the Lanham Act claim, it is not an element of Ice Cube's right of publicity claims under California law. Although the opinion doesn't address the issue, presumably the court also dismissed the right of publicity claims because it didn't consider the newsletter to be an advertisement and, therefore, didn't view the use of Ice Cube's image as a use for "purposes of advertising."

If Ice Cube decides to file an amended complaint, he likely will try to allege facts to bolster his position that the newsletter is not editorial content but instead is advertising or, at least, an "advertisement in disguise." See, e.g., Beverley v. Choices Women’s Medical Center, Inc. (use of the plaintiff's photo in a calendar designed to promote a Queens medical facility was an advertising use under New York's right of publicity statute); cf. Facenda v. NFL Films, Inc. (TV program about the "making of" an NFL-licensed video game that was produced by NFL, telecast on NFL network, included only positive coverage and featured countdown clock for release of video game was commercial speech) and Downing v. Abercrombie & Fitch (rejecting First Amendment defense to right of publicity claim asserted by surfer whose photo was used to illustrate a surfer-themed article included in a retailer's magazine-catalog). Based on Magistrate Judge Beeler's opinion, Ice Cube is going to have his work cut out for him. There is nothing in the newsletter that expressly promotes Robinhood; indeed, the content of the newsletter is no different (I would imagine) from content published by financial news publications that unquestionably are editorial and entitled to full protection under the First Amendment. One way to frame the question, if this case goes forward: are the newsletters primarily vehicles to promote (even if indirectly, like a brand equity ad) Robinhood and its services? Or are the newsletters, in essence, a separate editorial product that Robinhood publishes? (The fact that, in 2019, Robinhood acquired the company that originally published the newsletter may support that the newsletter is a separate and independent product.) Ice Cube's success may ultimately turn on this question.

Jackson v. Robinhood Markets, Inc.,

No. 21-cv-02304-LB, 2021 WL 2435307 (N. D. Cal. June 15, 2

/Passle/5ca769f7abdfe80aa08edc04/SearchServiceImages/2024-12-16-16-35-24-812-676056cc044a44825e000520.jpg)

/Passle/5ca769f7abdfe80aa08edc04/MediaLibrary/Images/5d551c4d8cb62305fcfdcb14/2024-02-28-17-13-03-324-65df699ff4582f717c4118c2.png)

/Passle/5ca769f7abdfe80aa08edc04/MediaLibrary/Images/5d551c4d8cb62305fcfdcb14/2024-02-29-21-40-18-218-65e0f9c29a7e7ca6bd332946.jpg)